| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

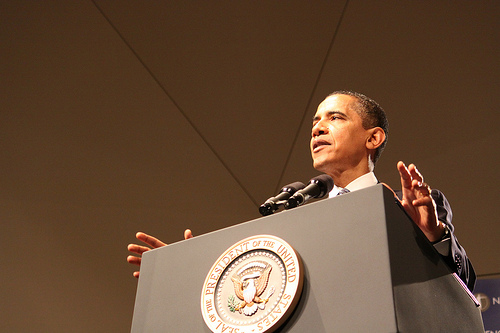

Obama subsequently announced that Varmus and MIT Biology professor Eric Lander would be co-chairs of PCAST, and in a February 27, 2009, address to the National Academy of Sciences, he announced his selection of the eighteen PCAST members.

Early on, Obama would also nominate Steven Chu, a Nobel Laureate in Physics and Director of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, as Secretary of Energy; Jane Lubchenco, a marine biologist from the University of Oregon, as director of NOAA; and NIH Human Genome Project Director Francis Collins as director of the National Institutes of Health. Chu and Lubchenco were the first scientists ever to occupy those positions.

On several occasions, Obama stressed his support for scientific research and education. Most noteworthy, in a November 27, 2009, address to the National Academy of Sciences, he promised to increase the R&D/GDP ratio to 3 percent by the end of his administration. In 2007, the U.S. R&D/GDP ratio was 2.67 percent, a decrease from its most recent high of 2.81 percent, in 2003. Since industry contributes almost 70 percent of national R&D expenditures as opposed to slightly less than 30 percent for the federal government, a substantial increase in the R&D/GDP ratio would require a substantial increase in industrial as well as federal expenditures.

A substantial increase in R&D investment, he emphasized, would contribute to the development of less expensive solar cells, learning software that could provide superior computer tutorials, and alternative, clean energy sources. “Energy,” he said, “is this generation’s great project.” He suggested that the United States commit itself to reduce carbon pollution by 50 percent by 2050. To this end, he announced the creation of the Advanced Research Project Agency for Energy—or ARPA-E, analogous to DARPA—in the Department of Energy. A transcript of Obama’s remarks at the National Academy of Sciences is available from that organization.

During his campaign, Obama had noted that bans on government funding for embryonic stem cell research harmed American competitiveness, as it impeded research into potential treatments for Parkinson’s, diabetes and Alzheimer’s. In March 2009, he ended a Bush-imposed eight-year ban on embryonic stem cell research utilizing cell lines created after August 9, 2001. He promised “strict oversight” of stem cell research and asked the National Institutes of Health to develop new guidelines. The president also instructed the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy to “develop a strategy for restoring scientific integrity” to government decision-making—a step designed to base science on “facts, not ideology.”

Of course, the president’s nomination of outstanding scientists to serve in his administration constituted a significant early policy action, as Neal Lane wrote approvingly in a Science editorial. Neal Lane, “Helping the President,” Science (April 10, 2009), 147. Lane pointed out that multiple senior advisers now had access to the president, and that his science advisor was only one among many to bring issues to his attention. Thus, the advisor had to cultivate close working relations with key senior White House officials, including the directors of OMB, the National Economic and Domestic Policy Advisors, and the National Security Council.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'A history of federal science policy from the new deal to the present' conversation and receive update notifications?