| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Fortunately, most stressors we encounter can be modified and are, to varying degrees, controllable. A person who cannot stand her job can quit and look for work elsewhere; a middle-aged divorcee can find another potential partner; the freshman who fails an exam can study harder next time, and a breast lump does not necessarily mean that one is fated to die of breast cancer.

The desire and ability to predict events, make decisions, and affect outcomes—that is, to enact control in our lives—is a basic tenet of human behavior (Everly&Lating, 2002). Albert Bandura (1997) stated that “the intensity and chronicity of human stress is governed largely by perceived control over the demands of one’s life” (p. 262). As cogently described in his statement, our reaction to potential stressors depends to a large extent on how much control we feel we have over such things. Perceived control is our beliefs about our personal capacity to exert influence over and shape outcomes, and it has major implications for our health and happiness (Infurna&Gerstorf, 2014). Extensive research has demonstrated that perceptions of personal control are associated with a variety of favorable outcomes, such as better physical and mental health and greater psychological well-being (Diehl&Hay, 2010). Greater personal control is also associated with lower reactivity to stressors in daily life. For example, researchers in one investigation found that higher levels of perceived control at one point in time were later associated with lower emotional and physical reactivity to interpersonal stressors (Neupert, Almeida,&Charles, 2007). Further, a daily diary study with 34 older widows found that their stress and anxiety levels were significantly reduced on days during which the widows felt greater perceived control (Ong, Bergeman,&Bisconti, 2005).

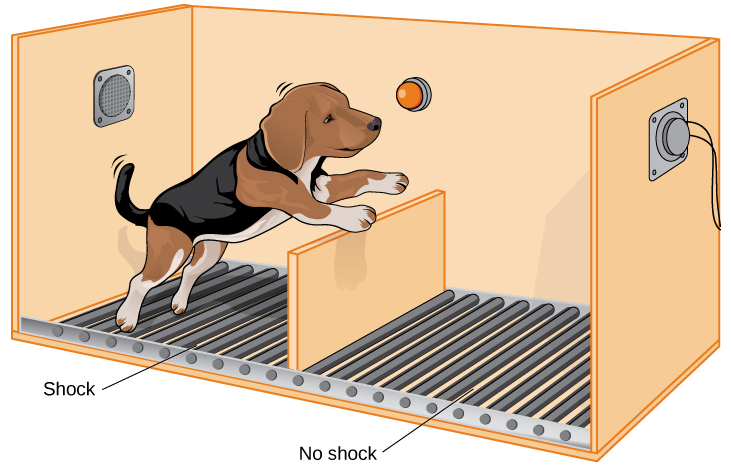

When we lack a sense of control over the events in our lives, particularly when those events are threatening, harmful, or noxious, the psychological consequences can be profound. In one of the better illustrations of this concept, psychologist Martin Seligman conducted a series of classic experiments in the 1960s (Seligman&Maier, 1967) in which dogs were placed in a chamber where they received electric shocks from which they could not escape. Later, when these dogs were given the opportunity to escape the shocks by jumping across a partition, most failed to even try; they seemed to just give up and passively accept any shocks the experimenters chose to administer. In comparison, dogs who were previously allowed to escape the shocks tended to jump the partition and escape the pain ( [link] ).

Seligman believed that the dogs who failed to try to escape the later shocks were demonstrating learned helplessness : They had acquired a belief that they were powerless to do anything about the noxious stimulation they were receiving. Seligman also believed that the passivity and lack of initiative these dogs demonstrated was similar to that observed in human depression. Therefore, Seligman speculated that acquiring a sense of learned helplessness might be an important cause of depression in humans: Humans who experience negative life events that they believe they are unable to control may become helpless. As a result, they give up trying to control or change the situation and some may become depressed and show lack of initiative in future situations in which they can control the outcomes (Seligman, Maier,&Geer, 1968).

Seligman and colleagues later reformulated the original learned helplessness model of depression (Abramson, Seligman,&Teasdale, 1978). In their reformulation, they emphasized attributions (i.e., a mental explanation for why something occurred) that lead to the perception that one lacks control over negative outcomes are important in fostering a sense of learned helplessness. For example, suppose a coworker shows up late to work; your belief as to what caused the coworker’s tardiness would be an attribution (e.g., too much traffic, slept too late, or just doesn’t care about being on time).

The reformulated version of Seligman’s study holds that the attributions made for negative life events contribute to depression. Consider the example of a student who performs poorly on a midterm exam. This model suggests that the student will make three kinds of attributions for this outcome: internal vs. external (believing the outcome was caused by his own personal inadequacies or by environmental factors), stable vs. unstable (believing the cause can be changed or is permanent), and global vs. specific (believing the outcome is a sign of inadequacy in most everything versus just this area). Assume that the student makes an internal (“I’m just not smart”), stable (“Nothing can be done to change the fact that I’m not smart”) and global (“This is another example of how lousy I am at everything”) attribution for the poor performance. The reformulated theory predicts that the student would perceive a lack of control over this stressful event and thus be especially prone to developing depression. Indeed, research has demonstrated that people who have a tendency to make internal, global, and stable attributions for bad outcomes tend to develop symptoms of depression when faced with negative life experiences (Peterson&Seligman, 1984).

Seligman’s learned helplessness model has emerged over the years as a leading theoretical explanation for the onset of major depressive disorder. When you study psychological disorders, you will learn more about the latest reformulation of this model—now called hopelessness theory.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Psychology' conversation and receive update notifications?