| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

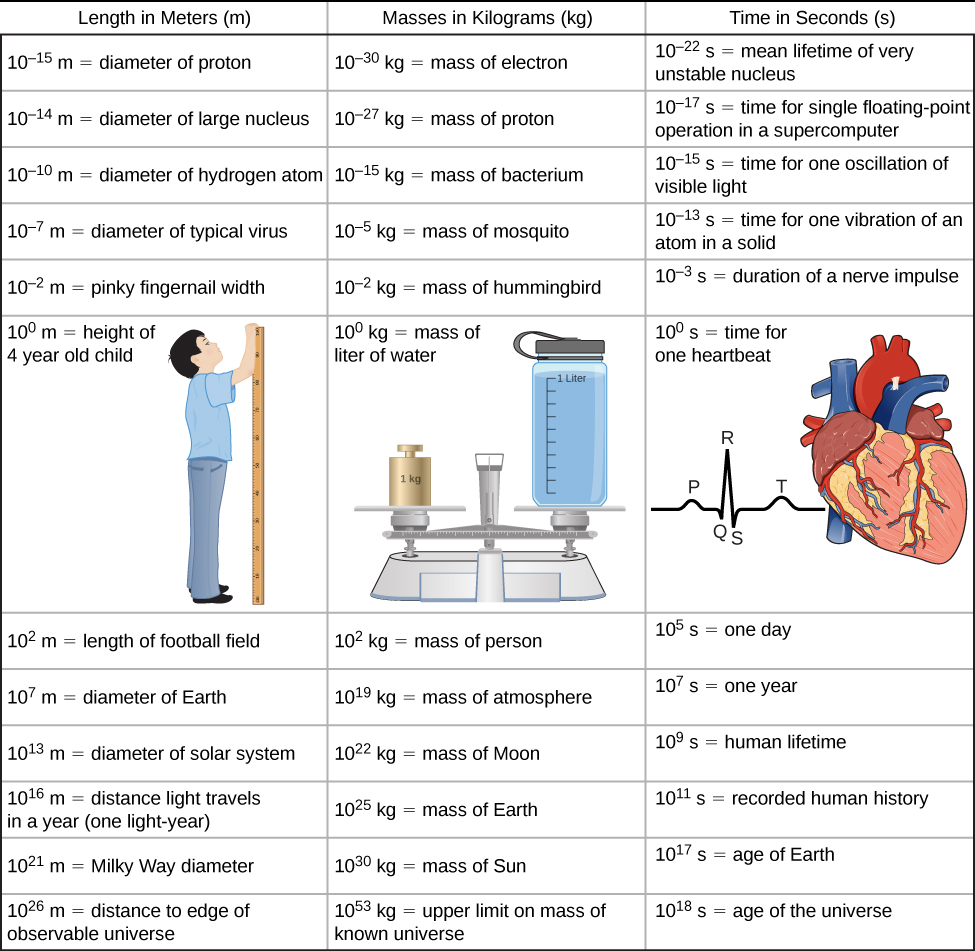

In studying [link] , take some time to come up with similar questions that interest you and then try answering them. Doing this can breathe some life into almost any table of numbers.

Visit this site to explore interactively the vast range of length scales in our universe. Scroll down and up the scale to view hundreds of organisms and objects, and click on the individual objects to learn more about each one.

How did we come to know the laws governing natural phenomena? What we refer to as the laws of nature are concise descriptions of the universe around us. They are human statements of the underlying laws or rules that all natural processes follow. Such laws are intrinsic to the universe; humans did not create them and cannot change them. We can only discover and understand them. Their discovery is a very human endeavor, with all the elements of mystery, imagination, struggle, triumph, and disappointment inherent in any creative effort ( [link] ). The cornerstone of discovering natural laws is observation; scientists must describe the universe as it is, not as we imagine it to be.

A model is a representation of something that is often too difficult (or impossible) to display directly. Although a model is justified by experimental tests, it is only accurate in describing certain aspects of a physical system. An example is the Bohr model of single-electron atoms, in which the electron is pictured as orbiting the nucleus, analogous to the way planets orbit the Sun ( [link] ). We cannot observe electron orbits directly, but the mental image helps explain some of the observations we can make, such as the emission of light from hot gases (atomic spectra). However, other observations show that the picture in the Bohr model is not really what atoms look like. The model is “wrong,” but is still useful for some purposes. Physicists use models for a variety of purposes. For example, models can help physicists analyze a scenario and perform a calculation or models can be used to represent a situation in the form of a computer simulation. Ultimately, however, the results of these calculations and simulations need to be double-checked by other means—namely, observation and experimentation.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'University physics volume 1' conversation and receive update notifications?