| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

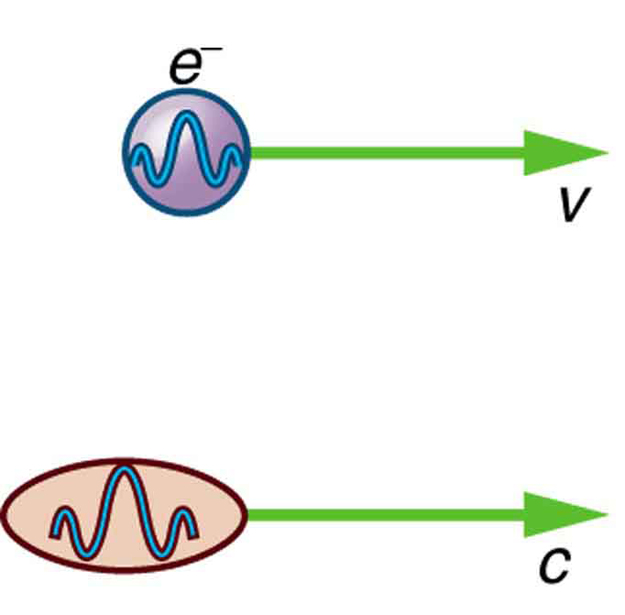

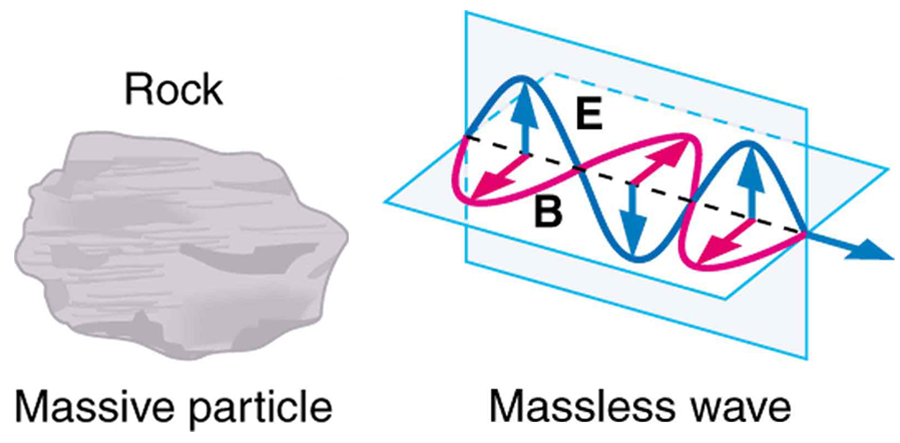

Particle-wave duality —the fact that all particles have wave properties—is one of the cornerstones of quantum mechanics. We first came across it in the treatment of photons, those particles of EM radiation that exhibit both particle and wave properties, but not at the same time. Later it was noted that particles of matter have wave properties as well. The dual properties of particles and waves are found for all particles, whether massless like photons, or having a mass like electrons. (See [link] .)

There are many submicroscopic particles in nature. Most have mass and are expected to act as particles, or the smallest units of matter. All these masses have wave properties, with wavelengths given by the de Broglie relationship . So, too, do combinations of these particles, such as nuclei, atoms, and molecules. As a combination of masses becomes large, particularly if it is large enough to be called macroscopic, its wave nature becomes difficult to observe. This is consistent with our common experience with matter.

Some particles in nature are massless. We have only treated the photon so far, but all massless entities travel at the speed of light, have a wavelength, and exhibit particle and wave behaviors. They have momentum given by a rearrangement of the de Broglie relationship, . In large combinations of these massless particles (such large combinations are common only for photons or EM waves), there is mostly wave behavior upon detection, and the particle nature becomes difficult to observe. This is also consistent with experience. (See [link] .)

The particle-wave duality is a universal attribute. It is another connection between matter and energy. Not only has modern physics been able to describe nature for high speeds and small sizes, it has also discovered new connections and symmetries. There is greater unity and symmetry in nature than was known in the classical era—but they were dreamt of. A beautiful poem written by the English poet William Blake some two centuries ago contains the following four lines:

To see the World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?