| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Below the epidermis of eudicot leaves are layers of cells known as the mesophyll, or “middle leaf.” The mesophyll of most leaves typically contains two arrangements of parenchyma cells: the palisade parenchyma and spongy parenchyma ( [link] ). The palisade parenchyma (also called the palisade mesophyll) has column-shaped, tightly packed cells, and may be present in one, two, or three layers. Below the palisade parenchyma are loosely arranged cells of an irregular shape. These are the cells of the spongy parenchyma (or spongy mesophyll). The air space found between the spongy parenchyma cells allows gaseous exchange between the leaf and the outside atmosphere through the stomata. In aquatic plants, the intercellular spaces in the spongy parenchyma help the leaf float. Both layers of the mesophyll contain many chloroplasts. Guard cells are the only epidermal cells to contain chloroplasts.

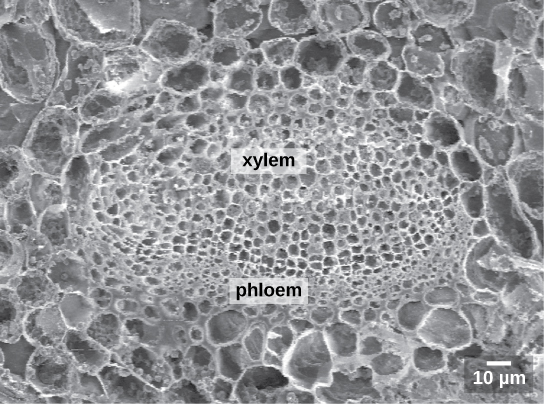

Like the stem, the leaf contains vascular bundles composed of xylem and phloem ( [link] ). The xylem consists of tracheids and vessels, which transport water and minerals to the leaves. The phloem transports the photosynthetic products from the leaf to the other parts of the plant. A single vascular bundle, no matter how large or small, always contains both xylem and phloem tissues.

Coniferous plant species that thrive in cold environments, like spruce, fir, and pine, have leaves that are reduced in size and needle-like in appearance. These needle-like leaves have sunken stomata and a smaller surface area: two attributes that aid in reducing water loss. In hot climates, plants such as cacti have succulent leaves that help to conserve water. Many aquatic plants have leaves with wide lamina that can float on the surface of the water, and a thick waxy cuticle on the leaf surface that repels water.

In tropical rainforests, light is often scarce, since many trees and plants grow close together and block much of the sunlight from reaching the forest floor. Many tropical plant species have exceptionally broad leaves to maximize the capture of sunlight. Other species are epiphytes: plants that grow on other plants that serve as a physical support. Such plants are able to grow high up in the canopy atop the branches of other trees, where sunlight is more plentiful. Epiphytes live on rain and minerals collected in the branches and leaves of the supporting plant. Bromeliads (members of the pineapple family), ferns, and orchids are examples of tropical epiphytes ( [link] ). Many epiphytes have specialized tissues that enable them to efficiently capture and store water.

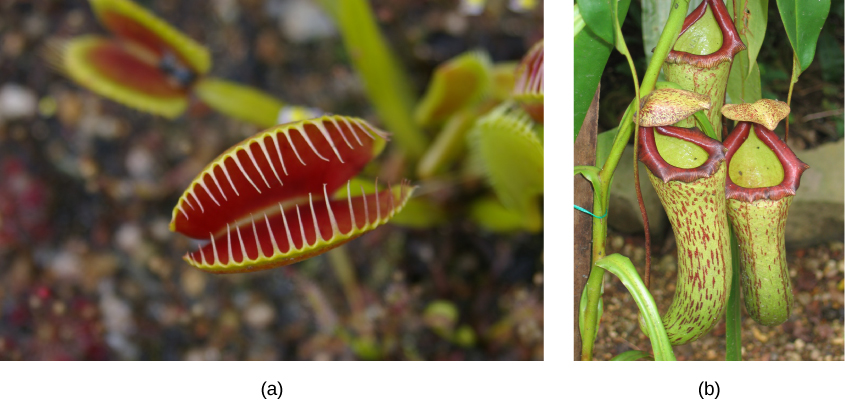

Some plants have special adaptations that help them to survive in nutrient-poor environments. Carnivorous plants, such as the Venus flytrap and the pitcher plant ( [link] ), grow in bogs where the soil is low in nitrogen. In these plants, leaves are modified to capture insects. The insect-capturing leaves may have evolved to provide these plants with a supplementary source of much-needed nitrogen.

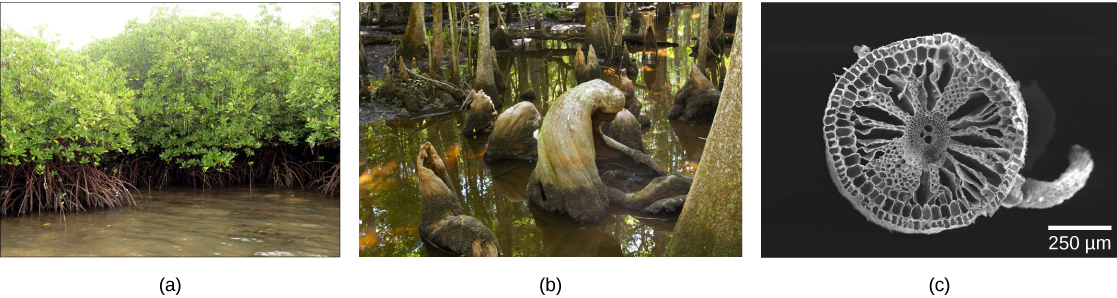

Many swamp plants have adaptations that enable them to thrive in wet areas, where their roots grow submerged underwater. In these aquatic areas, the soil is unstable and little oxygen is available to reach the roots. Trees such as mangroves ( Rhizophora sp.) growing in coastal waters produce aboveground roots that help support the tree ( [link] ). Some species of mangroves, as well as cypress trees, have pneumatophores: upward-growing roots containing pores and pockets of tissue specialized for gas exchange. Wild rice is an aquatic plant with large air spaces in the root cortex. The air-filled tissue—called aerenchyma—provides a path for oxygen to diffuse down to the root tips, which are embedded in oxygen-poor bottom sediments.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?