| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

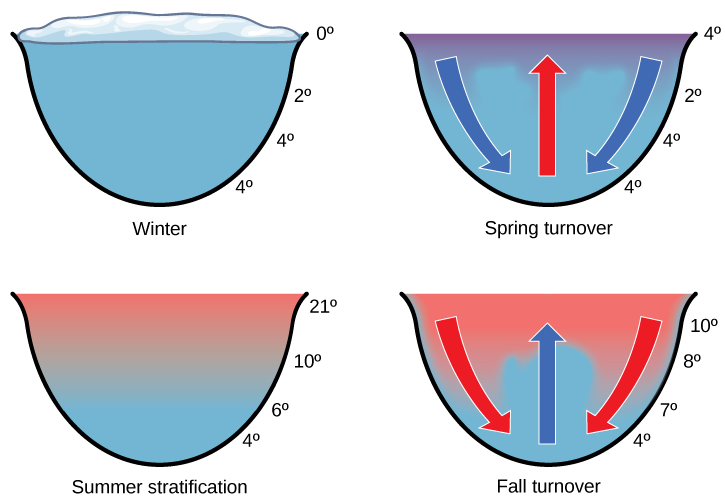

In springtime, air temperatures increase and surface ice melts. When the temperature of the surface water begins to reach 4 °C, the water becomes heavier and sinks to the bottom. The water at the bottom of the lake is then displaced by the heavier surface water and, thus, rises to the top. As that water rises to the top, the sediments and nutrients from the lake bottom are brought along with it. During the summer months, the lake water stratifies, or forms layers, with the warmest water at the lake surface.

As air temperatures drop in the fall, the temperature of the lake water cools to 4 °C; therefore, this causes fall turnover as the heavy cold water sinks and displaces the water at the bottom. The oxygen-rich water at the surface of the lake then moves to the bottom of the lake, while the nutrients at the bottom of the lake rise to the surface ( [link] ). During the winter, the oxygen at the bottom of the lake is used by decomposers and other organisms requiring oxygen, such as fish.

In addition to its effects on the density of water, temperature affects the physiology (and the biogeographic distribution) of living things. Temperature exerts an important influence on living things because few organisms can survive at temperatures below 0° C (32° F), due to metabolic constraints. It is also rare for living things to survive at temperatures exceeding 45° C (113° F). This is primarily due to temperature effects on the proteins known as enzymes. Enzymes are typically most efficient within a narrow and specific range of temperatures; enzyme denaturation (damage) can occur at higher temperatures, and enzymes do not work fast enough at lower temperatures. Therefore, organisms either must maintain an internal temperature that keeps their enzymes functioning, or they must inhabit an environment that will keep the body within a temperature range that supports metabolism. Some animals have adapted to enable their bodies to survive significant temperature fluctuations. Some Antarctic fish live at temperatures below freezing, and hibernating Arctic ground squirrels ( Urocitellus parryii ) can survive if their body temperature drops below freezing. Similarly, some bacteria are adapted to surviving in extremely hot environments, such as geysers, boiling mud pits or deep-ocean hydrothermal vents. Such bacteria are examples of extremophiles: organisms that thrive in extreme environments.

Temperature can also limit the distribution of living things. Animals in regions with large temperature fluctuations may respond with various adaptations, such as migration, in order to survive. Migration, the movement from one place to another, is an adaptation found in many animals, including many that inhabit seasonally cold climates. Migration solves problems related to temperature, locating food, and finding a mate. In migration, for instance, the Arctic Tern ( Sterna paradisaea ) makes a 40,000 km (24,000 mi) round trip flight each year between its feeding grounds in the southern hemisphere and its breeding grounds in the Arctic. Monarch butterflies ( Danaus plexippus ) live in the eastern United States in the warmer months and migrate to Mexico and the southern United States in the wintertime. Some species of mammals also make migratory forays. Reindeer ( Rangifer tarandus ) travel about 5,000 km (3,100 mi) each year to find food. Amphibians and reptiles are more limited in their distribution because they lack migratory ability. Not all animals that can migrate do so: migration carries risk and comes at a high energy cost.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?