| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

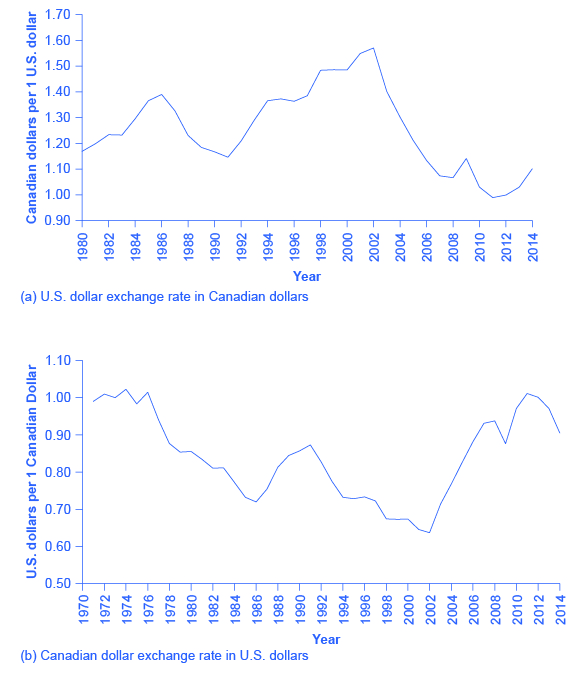

In looking at the exchange rate between two currencies, the appreciation or strengthening of one currency must mean the depreciation or weakening of the other. [link] (b) shows the exchange rate for the Canadian dollar, measured in terms of U.S. dollars. The exchange rate of the U.S. dollar measured in Canadian dollars, shown in [link] (a), is a perfect mirror image with the exchange rate of the Canadian dollar measured in U.S. dollars, shown in [link] (b). A fall in the Canada $/U.S. $ ratio means a rise in the U.S. $/Canada $ ratio, and vice versa.

With the price of a typical good or service, it is clear that higher prices benefit sellers and hurt buyers, while lower prices benefit buyers and hurt sellers. In the case of exchange rates, where the buyers and sellers are not always intuitively obvious, it is useful to trace through how different participants in the market will be affected by a stronger or weaker currency. Consider, for example, the impact of a stronger U.S. dollar on six different groups of economic actors, as shown in [link] : (1) U.S. exporters selling abroad; (2) foreign exporters (that is, firms selling imports in the U.S. economy); (3) U.S. tourists abroad; (4) foreign tourists visiting the United States; (5) U.S. investors (either foreign direct investment or portfolio investment) considering opportunities in other countries; (6) and foreign investors considering opportunities in the U.S. economy.

For a U.S. firm selling abroad, a stronger U.S. dollar is a curse. A strong U.S. dollar means that foreign currencies are correspondingly weak. When this exporting firm earns foreign currencies through its export sales, and then converts them back to U.S. dollars to pay workers, suppliers, and investors, the stronger dollar means that the foreign currency buys fewer U.S. dollars than if the currency had not strengthened, and that the firm’s profits (as measured in dollars) fall. As a result, the firm may choose to reduce its exports, or it may raise its selling price, which will also tend to reduce its exports. In this way, a stronger currency reduces a country’s exports.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of macroeconomics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?