| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

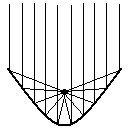

What good are parabolas? We’ve already seen some use for graphing parabolas, in terms of modeling certain kinds of behavior. If I throw a ball into the air, not straight up, its path through the air is a parabola. But here is another cool thing: if parallel lines come into a parabola, they all bounce to the focus.

So telescopes are made by creating parabolic mirrors —all the incoming light is concentrated at the focus. Pretty cool, huh?

We are already somewhat familiar with parabola machinery. We recall that the equation for a vertical parabola is and the equation for a horizontal parabola is . The vertex in either case is at ( , ). We also recall that if a is positive, it opens up (vertical) or to the right (horizontal); if a is negative, it opens down or to the left. This is all old news.

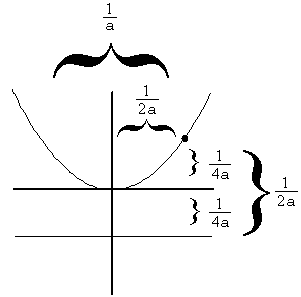

Thus far, whenever we have graphed parabolas, we have found the vertex, determined whether they open up or down or right or left, and then gone “swoosh.” If we were a little more sophisticated, we remembered that the width of the parabola was determined by ; so is narrower than which is narrower than . But how can we use a to actually draw the width accurately? That is the question for today. And the answer starts out with one fact which may seem quite unrelated: the distance from the vertex to the focus is . I’m going to present this as a magical fact for the moment—we will never prove it, though we will demonstrate it for a few examples. But that one little fact is the only thing I am going to ask you to “take my word for”—everything else is going to flow logically from that.

(Go back to your drawing of our parabola with focus (0,3) and directrix , and point out the distance from vertex to focus—label it .) Now, what is the distance from the vertex to the directrix? Someone should get this: it must also be . Why? Because the vertex is part of the parabola, so by definition, it must be the same distance from the directrix that it is from the focus. Label that.

Now, let’s start at this point here (point to (-6,3)) and go down to the directrix. How long is that? Again, someone should get it: , which is or . Now, how far over is it, from this same point to the focus? Well, again, this is on the parabola, so it must be the same distance to the focus that it is to the directrix: .

If you extend that line all the way to the other side, you have two of those: , or , running between (6,3) and (–6,3). This line is called the latus rectum —Latin for “straight line”—it is always a line that touches the parabola at two points, runs parallel to the directrix, and goes through the focus.

At this point, the blackboard looks something like this:

The point should be clear. Starting with the one magical fact that the distance from the focus to the vertex is , we can get everything else, including the length of the latus rectum, . And that gives us a way of doing exactly what we wanted, which is using a to more accurately draw a parabola.

At this point, you do a sample problem on the board, soup to nuts. Say, . They should be able to see quickly that it is horizontal, opens to the right, with vertex at (-4,-3)—that’s all review. But now we can also say that the distance from the focus to the vertex is which in this case (since ) is . So where is the focus? Draw the parabola quickly on the board. They should be able to see that the focus is to the right of the vertex, so that puts us at( , ). The directrix is to the left, at . (I always warn them at this point, a very common way to miss points on the test is to say that the directrix is ( , ). That’s a point—the directrix is a line!)

How wide is the parabola? When we graphed them before, we had no way of determining that: but now we have the latus rectum to help us out. The length of the latus rectum is which is 2. So you can draw that in around the focus—going up one and down one—and then draw the parabola more accurately, staring from the focus and touching the latus rectum on both sides.

Whew! Got all that? Good then, you’re ready for the homework! (You may want to mention that a different sample problem is worked in the “Conceptual Explanations.”)

This one will take a lot of debriefing afterwards. Let’s talk about #3 for a minute. The first thing they should have done is draw it—that can’t be stressed enough—always draw it! Drawing the vertex and focus, they should be able to see that the parabola opens to the right. Since we know the vertex, we can write immediately . Many of them will have gotten that far, and then gotten stuck. Show them that the distance from the vertex to the focus is 2, and we know that this distance must be , so . We can solve this to find which fills in the final piece of the puzzle.

On #5, again, before doing anything else, they should draw it! They should see that there is one vertical and one horizontal parabola that fits this definition.

But how can they find them? You do the vertical, they can do the horizontal. Knowing the vertex, we know that the vertical one will look like . How can we find a this time, by using the information that it “contains the point (0,1)”? Well, we have to go back to our last unit, when we found the equation for a parabola containing certain points! Remember, we said that if it contains a point, then that point must make the equation true! So we can plug in (0,1) to the equation, and solve for . , , . The negative tells us that the parabola will open down—and our drawing already told us that, so that’s a good reality check.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Advanced algebra ii: teacher's guide' conversation and receive update notifications?