| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

We have developed macroscopic definitions of pressure and temperature. Pressure is the force divided by the area on which the force is exerted, and temperature is measured with a thermometer. We gain a better understanding of pressure and temperature from the kinetic theory of gases, which assumes that atoms and molecules are in continuous random motion.

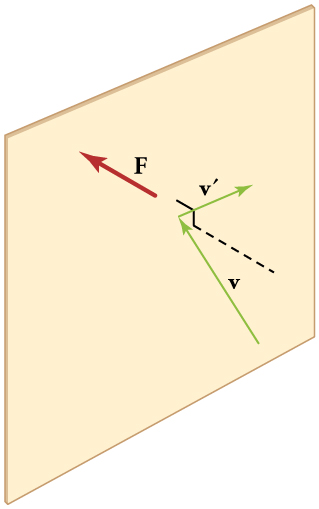

[link] shows an elastic collision of a gas molecule with the wall of a container, so that it exerts a force on the wall (by Newton’s third law). Because a huge number of molecules will collide with the wall in a short time, we observe an average force per unit area. These collisions are the source of pressure in a gas. As the number of molecules increases, the number of collisions and thus the pressure increase. Similarly, the gas pressure is higher if the average velocity of molecules is higher. The actual relationship is derived in the Things Great and Small feature below. The following relationship is found:

where is the pressure (average force per unit area), is the volume of gas in the container, is the number of molecules in the container, is the mass of a molecule, and is the average of the molecular speed squared.

What can we learn from this atomic and molecular version of the ideal gas law? We can derive a relationship between temperature and the average translational kinetic energy of molecules in a gas. Recall the previous expression of the ideal gas law:

Equating the right-hand side of this equation with the right-hand side of gives

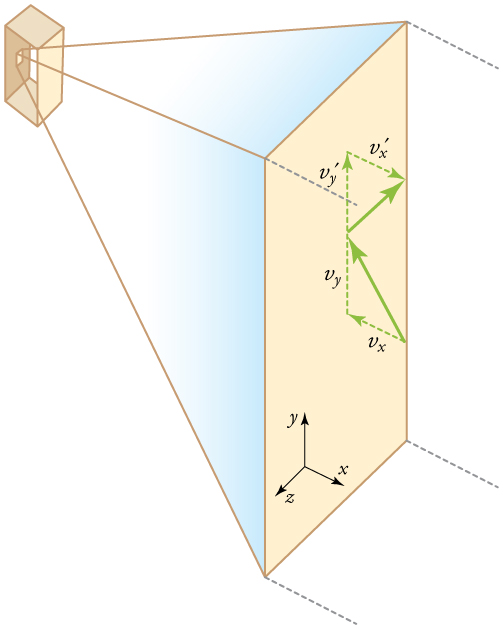

[link] shows a box filled with a gas. We know from our previous discussions that putting more gas into the box produces greater pressure, and that increasing the temperature of the gas also produces a greater pressure. But why should increasing the temperature of the gas increase the pressure in the box? A look at the atomic and molecular scale gives us some answers, and an alternative expression for the ideal gas law.

The figure shows an expanded view of an elastic collision of a gas molecule with the wall of a container. Calculating the average force exerted by such molecules will lead us to the ideal gas law, and to the connection between temperature and molecular kinetic energy. We assume that a molecule is small compared with the separation of molecules in the gas, and that its interaction with other molecules can be ignored. We also assume the wall is rigid and that the molecule’s direction changes, but that its speed remains constant (and hence its kinetic energy and the magnitude of its momentum remain constant as well). This assumption is not always valid, but the same result is obtained with a more detailed description of the molecule’s exchange of energy and momentum with the wall.

If the molecule’s velocity changes in the -direction, its momentum changes from to . Thus, its change in momentum is . The force exerted on the molecule is given by

There is no force between the wall and the molecule until the molecule hits the wall. During the short time of the collision, the force between the molecule and wall is relatively large. We are looking for an average force; we take to be the average time between collisions of the molecule with this wall. It is the time it would take the molecule to go across the box and back (a distance at a speed of . Thus , and the expression for the force becomes

This force is due to one molecule. We multiply by the number of molecules and use their average squared velocity to find the force

where the bar over a quantity means its average value. We would like to have the force in terms of the speed , rather than the -component of the velocity. We note that the total velocity squared is the sum of the squares of its components, so that

Because the velocities are random, their average components in all directions are the same:

Thus,

or

Substituting into the expression for gives

The pressure is so that we obtain

where we used for the volume. This gives the important result.

This equation is another expression of the ideal gas law.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Physics 101' conversation and receive update notifications?