| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Earthquakes, essentially sound waves in Earth’s crust, are an interesting example of how the speed of sound depends on the rigidity of the medium. Earthquakes have both longitudinal and transverse components, and these travel at different speeds. The bulk modulus of granite is greater than its shear modulus. For that reason, the speed of longitudinal or pressure waves (P-waves) in earthquakes in granite is significantly higher than the speed of transverse or shear waves (S-waves). Both components of earthquakes travel slower in less rigid material, such as sediments. P-waves have speeds of 4 to 7 km/s, and S-waves correspondingly range in speed from 2 to 5 km/s, both being faster in more rigid material. The P-wave gets progressively farther ahead of the S-wave as they travel through Earth’s crust. The time between the P- and S-waves is routinely used to determine the distance to their source, the epicenter of the earthquake.

The speed of sound is affected by temperature in a given medium. For air at sea level, the speed of sound is given by

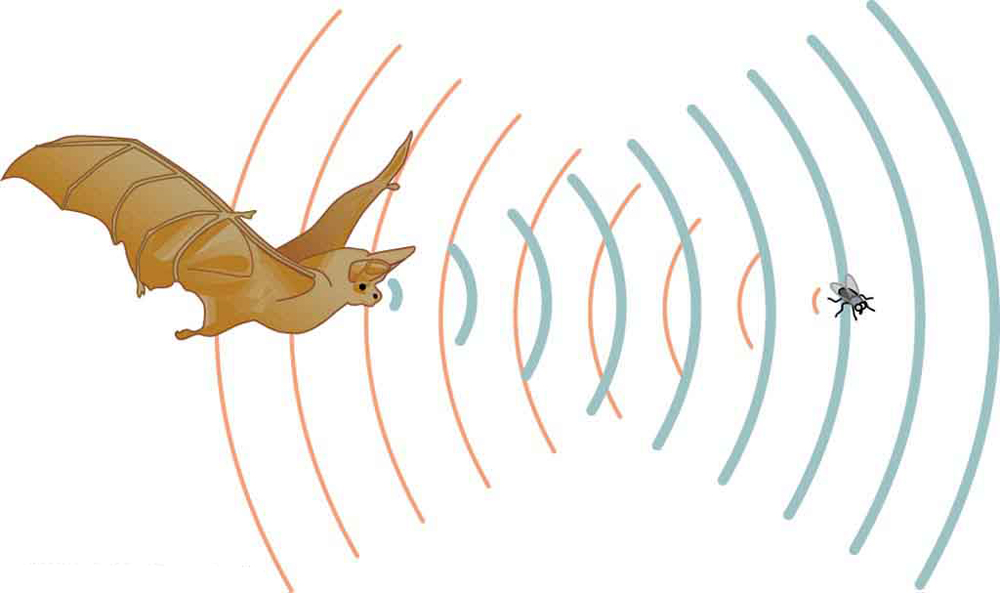

where the temperature (denoted as ) is in units of kelvin. While not negligible, this is not a strong dependence. At , the speed of sound is 331 m/s, whereas at it is 343 m/s, less than a 4% increase. [link] shows a use of the speed of sound by a bat to sense distances. Echoes are also used in medical imaging.

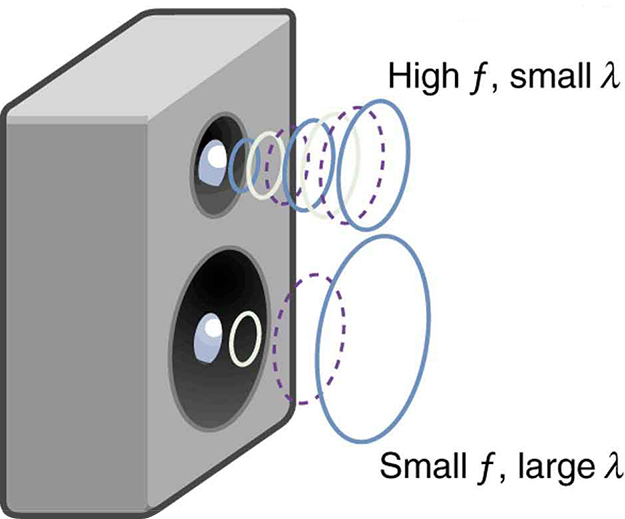

One of the more important properties of sound is that its speed is nearly independent of frequency. This independence is certainly true in open air for sounds in the audible range of 20 to 20,000 Hz. If this independence were not true, you would certainly notice it for music played by a marching band in a football stadium, for example. Suppose that high-frequency sounds traveled faster—then the farther you were from the band, the more the sound from the low-pitch instruments would lag that from the high-pitch ones. But the music from all instruments arrives in cadence independent of distance, and so all frequencies must travel at nearly the same speed. Recall that

In a given medium under fixed conditions, is constant, so that there is a relationship between and ; the higher the frequency, the smaller the wavelength. See [link] and consider the following example.

Calculate the wavelengths of sounds at the extremes of the audible range, 20 and 20,000 Hz, in air. (Assume that the frequency values are accurate to two significant figures.)

Strategy

To find wavelength from frequency, we can use .

Solution

Discussion

Because the product of multiplied by equals a constant, the smaller is, the larger must be, and vice versa.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Concepts of physics with linear momentum' conversation and receive update notifications?