| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

A journey to brazil, 1853

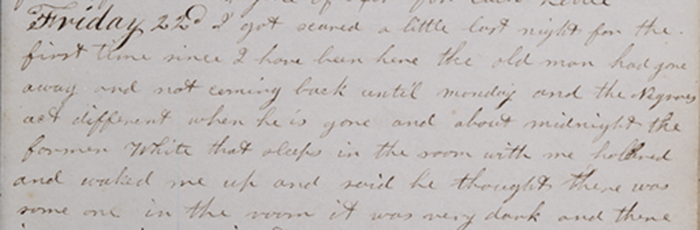

While the implications of revolutionary violence in the journal jump out the most to a contemporary reader, Dunham touches upon other forms of slave resistance that are worth noting. He observes behavior among some of the slaves that he seems to interpret as laziness, stating, “there is several negroes lying round sick and some do not appear as sick as they pretend” (89). Many historians of New World slavery have pointed to the pretence of sickness and the refusal to work among slaves as a subtle and effective form of protest, given the circumstances. Slave owners and drivers would, of course, write this behavior off as mere laziness and further evidence of the racial inferiority of blacks to whites. Determining the agency of individual slaves within a system designed to render them so powerless has been a demanding endeavor for these scholars, and primary texts such as A Journey to Brazil are crucial in piecing together a comprehensive narrative of slave systems and all their players. Yet another moment that shines a light on the unrest of Brazilian slaves comes in a brief but telling passage: “Three young negroes that belong here took each of them a horse out of the barn here Tuesday night to ride off somewhere and the German that has charge here caught two of them that night and the other run into the woods or some other place and has not come back yet” (109). The history of runaway slaves in the U.S. is a familiar one, primarily represented by the Underground Railroad and its most famous actor, Harriet Tubman. This phenomenon was a common one throughout the slaveholding Americas, resulting in a widespread community of runaway slaves known as “maroons.” Maroons would often flee to mountainous or swampy terrain (not easily accessible to the planters), and they were frequently implicated in the fomenting of anti-slavery conspiracy and potential insurrection.

Utilizing this approach to Dunham’s journal should produce great rewards for the U.S. literature instructor, in particular. The above passages from Journey to Brazil can be productively paired with any number of important literary works that touch upon the topic of slave rebellion. Frederick Douglass’s short story “The Heroic Slave” (1852) chronicles the true-life events of a revolt on board the slave ship Creole , led by a slave named Madison Washington. The story concludes with the commandeering of the ship by the freed slaves and their successful escape to an island in the recently emancipated British Caribbean, gesturing toward the hemispheric entanglements of slavery and emancipation in the nineteenth century. Benito Cereno (1856), the famous novella by Herman Melville, operates similarly to “The Heroic Slave,” recounting an actual overthrow of a slave ship by its cargo, though in this instance the slaves are recaptured and either resold or sentenced to execution for their “crimes.” Eric Sundquist convincingly argues Melville’s narrative as a sort of metaphorical re-staging of the Haitian Revolution, designed to demonstrate the violence and injustice inherent to the institution of slavery. Of particular interest to a reader of the Dunham travel journal might be Martin Delany’s complex, fragmented novel Blake; or, The Huts of America (1859). The protagonist of Blake evolves from a slave in the U.S. South to a revolutionary leader in colonial Cuba; the international machinations of Delany’s narrative – with its emphasis on travel, border crossings, and the transnational exchange of institutions and ideologies – mirrors many of the dynamics that we have been tracing in Dunham’s writing. Finally, one cannot forget Harriet Beecher Stowe’s follow-up to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp (1856). Many radical abolitionists criticized Uncle Tom’s Cabin for a lack of revolutionary content, claiming that its black characters were too passive in the acceptance of their lot. Stowe attempted to answer her critics with the character of Dred, a revolutionary maroon and descendent of Nat Turner living in the swamps and planning an insurrection (which never comes to fruition) against southern slavery.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Slavery in the americas' conversation and receive update notifications?