| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Infection with the gram-negative bacterium Francisella tularensis causes tularemia (or rabbit fever ), a zoonotic infection in humans. F. tularensis is a facultative intracellular parasite that primarily causes illness in rabbits, although a wide variety of domesticated animals are also susceptible to infection. Humans can be infected through ingestion of contaminated meat or, more typically, handling of infected animal tissues (e.g., skinning an infected rabbit). Tularemia can also be transmitted by the bites of infected arthropods, including the dog tick ( Dermacentor variabilis ), the lone star tick ( Amblyomma americanum ), the wood tick ( Dermacentor andersoni ), and deer flies ( Chrysops spp.). Although the disease is not directly communicable between humans, exposure to aerosols of F. tularensis can result in life-threatening infections. F. tularensis is highly contagious, with an infectious dose of as few as 10 bacterial cells. In addition, pulmonary infections have a 30%–60% fatality rate if untreated. World Health Organization. “WHO Guidelines on Tularaemia.” 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/resources/whotularemiamanual.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2016. For these reasons, F. tularensis is currently classified and must be handled as a biosafety level-3 (BSL-3) organism and as a potential biological warfare agent.

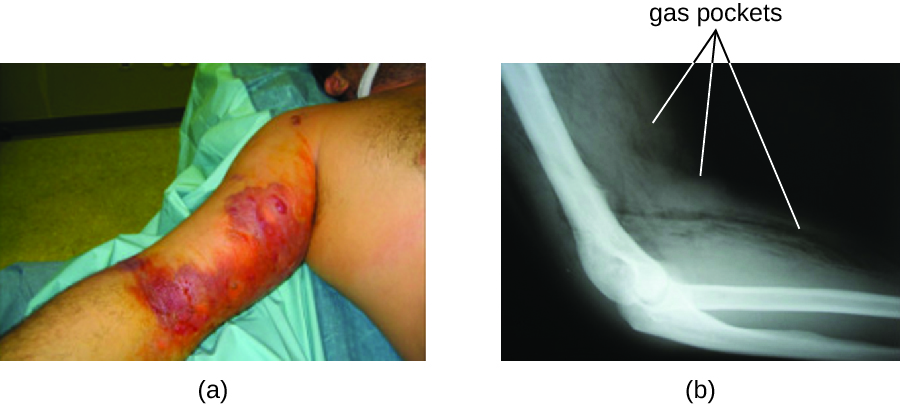

Following introduction through a break in the skin, the bacteria initially move to the lymph nodes, where they are ingested by phagocytes. After escaping from the phagosome, the bacteria grow and multiply intracellularly in the cytoplasm of phagocytes. They can later become disseminated through the blood to other organs such as the liver, lungs, and spleen, where they produce masses of tissue called granulomas ( [link] ). After an incubation period of about 3 days, skin lesions develop at the site of infection. Other signs and symptoms include fever, chills, headache, and swollen and painful lymph nodes.

A direct diagnosis of tularemia is challenging because it is so contagious. Once a presumptive diagnosis of tularemia is made, special handling is required to collect and process patients’ specimens to prevent the infection of health-care workers. Specimens suspected of containing F. tularensis can only be handled by BSL-2 or BSL-3 laboratories registered with the Federal Select Agent Program, and individuals handling the specimen must wear protective equipment and use a class II biological safety cabinet.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?