| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

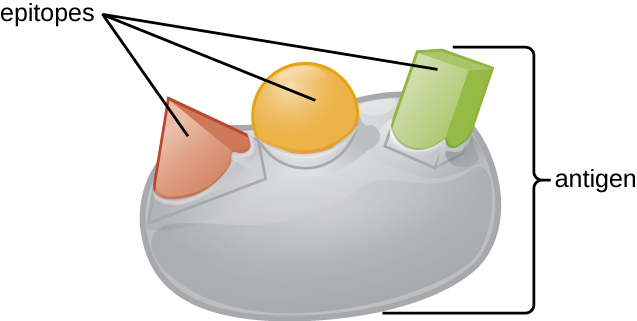

An antigen’s size is another important factor in its antigenic potential. Whereas large antigenic structures like flagella possess multiple epitopes, some molecules are too small to be antigenic by themselves. Such molecules, called haptens , are essentially free epitopes that are not part of the complex three-dimensional structure of a larger antigen. For a hapten to become antigenic, it must first attach to a larger carrier molecule (usually a protein) to produce a conjugate antigen. The hapten-specific antibodies produced in response to the conjugate antigen are then able to interact with unconjugated free hapten molecules. Haptens are not known to be associated with any specific pathogens, but they are responsible for some allergic responses. For example, the hapten urushiol , a molecule found in the oil of plants that cause poison ivy , causes an immune response that can result in a severe rash (called contact dermatitis). Similarly, the hapten penicillin can cause allergic reactions to drugs in the penicillin class.

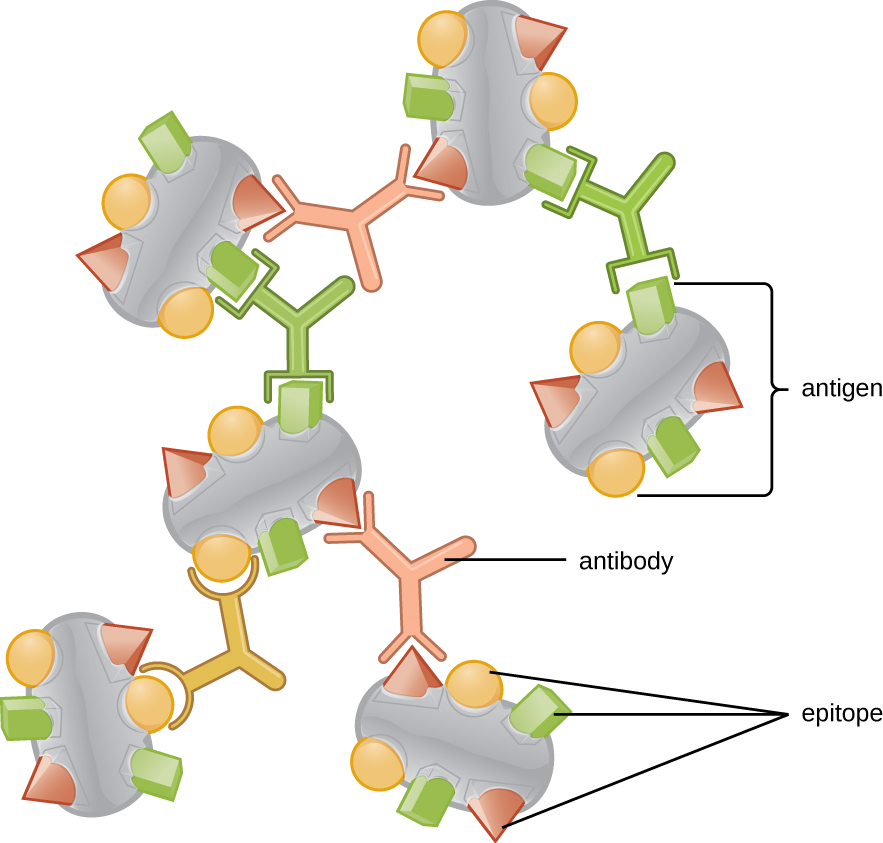

Antibodies (also called immunoglobulins) are glycoproteins that are present in both the blood and tissue fluids. The basic structure of an antibody monomer consists of four protein chains held together by disulfide bonds ( [link] ). A disulfide bond is a covalent bond between the sulfhydryl R groups found on two cysteine amino acids. The two largest chains are identical to each other and are called the heavy chains . The two smaller chains are also identical to each other and are called the light chains . Joined together, the heavy and light chains form a basic Y-shaped structure.

The two ‘arms’ of the Y-shaped antibody molecule are known as the Fab region , for “fragment of antigen binding.” The far end of the Fab region is the variable region, which serves as the site of antigen binding . The amino acid sequence in the variable region dictates the three-dimensional structure, and thus the specific three-dimensional epitope to which the Fab region is capable of binding. Although the epitope specificity of the Fab regions is identical for each arm of a single antibody molecule, this region displays a high degree of variability between antibodies with different epitope specificities. Binding to the Fab region is necessary for neutralization of pathogens, agglutination or aggregation of pathogens, and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

The constant region of the antibody molecule includes the trunk of the Y and lower portion of each arm of the Y. The trunk of the Y is also called the Fc region , for “fragment of crystallization,” and is the site of complement factor binding and binding to phagocytic cells during antibody-mediated opsonization .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?