| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Columbus’s 1493 letter—or probanza de mérito (proof of merit)—describing his “discovery” of a New World did much to inspire excitement in Europe. Probanzas de méritos were reports and letters written by Spaniards in the New World to the Spanish crown, designed to win royal patronage. Today they highlight the difficult task of historical work; while the letters are primary sources, historians need to understand the context and the culture in which the conquistadors, as the Spanish adventurers came to be called, wrote them and distinguish their bias and subjective nature. While they are filled with distortions and fabrications, probanzas de méritos are still useful in illustrating the expectation of wealth among the explorers as well as their view that native peoples would not pose a serious obstacle to colonization.

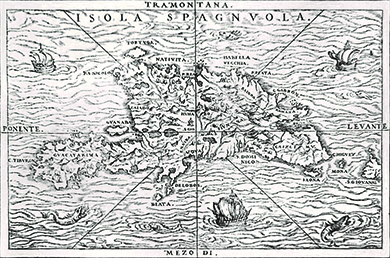

In 1493, Columbus sent two copies of a probanza de mérito to the Spanish king and queen and their minister of finance, Luis de Santángel. Santángel had supported Columbus’s voyage, helping him to obtain funding from Ferdinand and Isabella. Copies of the letter were soon circulating all over Europe, spreading news of the wondrous new land that Columbus had “discovered.” Columbus would make three more voyages over the next decade, establishing Spain’s first settlement in the New World on the island of Hispaniola. Many other Europeans followed in Columbus’s footsteps, drawn by dreams of winning wealth by sailing west. Another Italian, Amerigo Vespucci, sailing for the Portuguese crown, explored the South American coastline between 1499 and 1502. Unlike Columbus, he realized that the Americas were not part of Asia but lands unknown to Europeans. Vespucci’s widely published accounts of his voyages fueled speculation and intense interest in the New World among Europeans. Among those who read Vespucci’s reports was the German mapmaker Martin Waldseemuller. Using the explorer’s first name as a label for the new landmass, Waldseemuller attached “America” to his map of the New World in 1507, and the name stuck.

The exploits of the most famous Spanish explorers have provided Western civilization with a narrative of European supremacy and Indian savagery. However, these stories are based on the self-aggrandizing efforts of conquistadors to secure royal favor through the writing of probanzas de méritos (proofs of merit). Below are excerpts from Columbus’s 1493 letter to Luis de Santángel, which illustrates how fantastic reports from European explorers gave rise to many myths surrounding the Spanish conquest and the New World.

This island, like all the others, is most extensive. It has many ports along the sea-coast excelling any in Christendom—and many fine, large, flowing rivers. The land there is elevated, with many mountains and peaks incomparably higher than in the centre isle. They are most beautiful, of a thousand varied forms, accessible, and full of trees of endless varieties, so high that they seem to touch the sky, and I have been told that they never lose their foliage. . . . There is honey, and there are many kinds of birds, and a great variety of fruits. Inland there are numerous mines of metals and innumerable people. Hispaniola is a marvel. Its hills and mountains, fine plains and open country, are rich and fertile for planting and for pasturage, and for building towns and villages. The seaports there are incredibly fine, as also the magnificent rivers, most of which bear gold. The trees, fruits and grasses differ widely from those in Juana. There are many spices and vast mines of gold and other metals in this island. They have no iron, nor steel, nor weapons, nor are they fit for them, because although they are well-made men of commanding stature, they appear extraordinarily timid. The only arms they have are sticks of cane, cut when in seed, with a sharpened stick at the end, and they are afraid to use these. Often I have sent two or three men ashore to some town to converse with them, and the natives came out in great numbers, and as soon as they saw our men arrive, fled without a moment’s delay although I protected them from all injury.

What does this letter show us about Spanish objectives in the New World? How do you think it might have influenced Europeans reading about the New World for the first time?

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?