| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

A similar form of aggregating was also observed in salmon sharks (Lamna ditropis) gathered off the coast of Alaska, waiting for the salmon migration (Hulbert et al., 2005). The salmon sharks switched between focal foraging and foraging dispersal strategies as they hunted, but they never cooperatively hunted for salmon as a group. Thus it appears there is no affiliation between hunting strategies and size segregation in sharks; the only social factor observed were warning displays (Klimley et al., 2001).

Although sharks do not segregate into groups of cooperative hunters, it’s plausible that they might segregate themselves into groups of homogeneously sized individuals in order to protect themselves (Guttridge et al. 2009).

Since sharks aggregate due to overlapping dietary resources (Wetherbee&Cortes, 2004), it’s no surprise that pregnant leopard sharks ( Triakis semifasciata ) aggregate in Humboldt Bay, California in order to give birth in clumps of eelgrass (Ebert&Ebert, 2005). The eelgrass is abundant with fish eggs, an important food source for newborn juveniles (Ebert&Ebert, 2005). In a similar manner, bluntnose sevengill sharks ( N. cepediamus ) enter the bay to birth their young after other elasmobranches have left. Just like how the juvenile T. semifasciata feed on fish eggs in the eelgrass, newborn bluntnose sevengill sharks feed on other newborn elasmobranches, especially juvenile leopard sharks.

However, Heupel and Heuter were astonished to find, in 2002, that juvenile blacktip sharks ( Carcharhinus limbatus ), despite living in the nutrient rich nursery, aggregate in the northern end of the bay rather than in the center where the prey is densest. According to the behavioral patterns observed in other elasmobranches, the juveniles should have aggregated where the food was most abundant. Instead, for the first 6 months after birth, the juveniles concentrated themselves in the kernel, the area in the northern end of the nursery (Heupel et al, 2004). A more indepth study of juvenile blacktip sharks by Heupel and Simpfendorfer in 2005 revealed that the young C. limbatus were observed to make daily foraging trips into the midst of where prey was densest; however, instead of remaining there, they return to the northern end of the nursery. The repeated behavior indicates that there must be a direct fitness benefit involved with such behavior. The occasional larger elasmobranch in the prey-rich area of the nursery may be the source of such a behavior (Heupel&Simpfendorfer, 2005). In gathering together away from areas of high prey density and areas containing possible predators in large, they use increase their survival rate. Thus despite the fact that protective segregation only applies to juvenile elasmobranches, the behavior observed indicate that sharks do in fact gather in order to protect themselves.

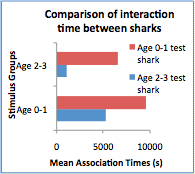

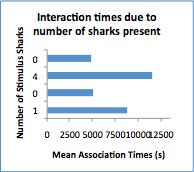

Both graphs are reproduced from Guttridge et al.'s (2009) data

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Mockingbird tales: readings in animal behavior' conversation and receive update notifications?