| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

As previously discussed, cowbird and cuckoo hosts exhibit different responses to learning their own eggs due to the specialist and generalist strategies of the two parasites. The result is that some species are far more willing to accept a parasitic egg than to reject it. Stokke et al. (2007) constructed a model to show how variation in egg appearance can affect whether a host species adopts an acceptor or rejecter approach. While acceptors accept all eggs, regardless of whether they are their own, rejecters will attempt to discriminate and reject parasitic eggs, risking misrecognition and rejection of own eggs. The model predicts that hosts that may potentially suffer greater losses from mistakes in recognition and rejection will be more likely to adopt an acceptor strategy. However, in cases where clutches have very similar eggs, hosts are more likely to reject since they are less likely to mistake their own eggs for a parasitic egg. The authors conclude that an increased learning period is more adaptive for clutches that have high variation between eggs since there is a greater risk of mistakes. A similar experiment corroborates these findings, revealing that females were much more successful at rejecting false eggs when mimicry is low and their eggs are more similar, situations in which learning one’s own eggs becomes more advantageous and the cost of losing an own egg is much lower (Rodriguez and Lotem 1999).

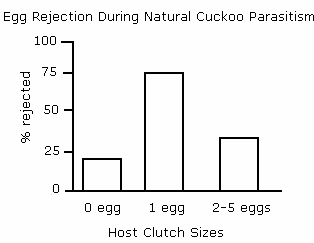

This dynamic ability of hosts to adjust their thresholds for egg acceptance or rejection is well-illustrated in one experiment by Moskat and Hauber (2007). Reed warblers reject cuckoo eggs more often when they had only laid one egg, but less often when several eggs or no eggs existed in the clutch ( [link] ). The authors hypothesized that reed warblers adjust their acceptance thresholds , or point at which eggs are accepted as own, based on the traits of the eggs in the clutch. When no eggs have been laid, the birds have no criteria on which to base their acceptance behavior. When only one egg has been laid, there are only a few traits that the hosts have to recognize as characteristic of their own eggs, so parasitic eggs that fall outside of this narrow range of traits are quickly rejected. However, as more eggs are laid by the host, variation between eggs results in a greater number of acceptable traits, and it becomes easier for a parasitic egg to slip in. To protect against mistaken rejection of their own eggs, hosts expand their acceptance thresholds to allow eggs with a greater variety of traits, resulting in greater acceptance of parasitic eggs as well. As predicted by Stokke et al., greater intraclutch variation , a greater difference between the eggs in the same clutch, prompted hosts to accept more eggs because the costs of misrecognition and misrejection increased. As a result, the birds were more willing to accept parasitic eggs than risk the loss from rejecting their own eggs

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Mockingbird tales: readings in animal behavior' conversation and receive update notifications?