| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

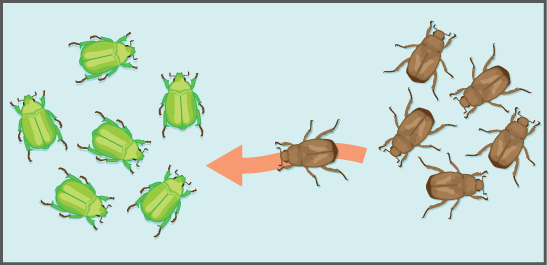

Another important evolutionary force is gene flow : the flow of alleles in and out of a population due to the migration of individuals or gametes ( [link] ). While some populations are fairly stable, others experience more flux. Many plants, for example, send their pollen far and wide, by wind or by bird, to pollinate other populations of the same species some distance away. Even a population that may initially appear to be stable, such as a pride of lions, can experience its fair share of immigration and emigration as developing males leave their mothers to seek out a new pride with genetically unrelated females. This variable flow of individuals in and out of the group not only changes the gene structure of the population, but it can also introduce new genetic variation to populations in different geological locations and habitats.

Mutations are changes to an organism’s DNA and are an important driver of diversity in populations. Species evolve because of the accumulation of mutations that occur over time. The appearance of new mutations is the most common way to introduce novel genotypic and phenotypic variance. Some mutations are unfavorable or harmful and are quickly eliminated from the population by natural selection. Others are beneficial and will spread through the population. Whether or not a mutation is beneficial or harmful is determined by whether it helps an organism survive to sexual maturity and reproduce. Some mutations do not do anything and can linger, unaffected by natural selection, in the genome. Some can have a dramatic effect on a gene and the resulting phenotype.

If individuals nonrandomly mate with their peers, the result can be a changing population. There are many reasons nonrandom mating occurs. One reason is simple mate choice; for example, female peahens may prefer peacocks with bigger, brighter tails. Traits that lead to more matings for an individual become selected for by natural selection. One common form of mate choice, called assortative mating , is an individual’s preference to mate with partners who are phenotypically similar to themselves. The increase in frequency of a particular allele because it is "sexy" is called sexual selection.

Another cause of nonrandom mating is physical location. This is especially true in large populations spread over large geographic distances where not all individuals will have equal access to one another. Some might be miles apart through woods or over rough terrain, while others might live immediately nearby.

Genes are not the only players involved in determining population variation. Phenotypes are also influenced by other factors, such as the environment ( [link] ). A beachgoer is likely to have darker skin than a city dweller, for example, due to regular exposure to the sun, an environmental factor. Some major characteristics, such as gender, are determined by the environment for some species. For example, some turtles and other reptiles have temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD). TSD means that individuals develop into males if their eggs are incubated within a certain temperature range, or females at a different temperature range.

Both genetic and environmental factors can cause phenotypic variation in a population. Different alleles can confer different phenotypes, and different environments can also cause individuals to look or act differently. Only those differences encoded in an individual’s genes, however, can be passed to its offspring and, thus, be a target of natural selection. Natural selection works by selecting for alleles that confer beneficial traits or behaviors, while selecting against those for deleterious qualities. Genetic drift stems from the chance occurrence that some individuals in the germ line have more offspring than others. When individuals leave or join the population, allele frequencies can change as a result of gene flow. Mutations to an individual’s DNA may introduce new variation into a population. Allele frequencies can also be altered when individuals do not randomly mate with others in the group.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'General biology part i - mixed majors' conversation and receive update notifications?