| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The formation of a solution is an example of a spontaneous process , a process that occurs under specified conditions without the requirement of energy from some external source. Sometimes we stir a mixture to speed up the dissolution process, but this is not necessary; a homogeneous solution would form if we waited long enough. The topic of spontaneity is critically important to the study of chemical thermodynamics and is treated more thoroughly in a later chapter of this text. For purposes of this chapter’s discussion, it will suffice to consider two criteria that favor , but do not guarantee, the spontaneous formation of a solution:

In the process of dissolution, an internal energy change often, but not always, occurs as heat is absorbed or evolved. An increase in disorder always results when a solution forms.

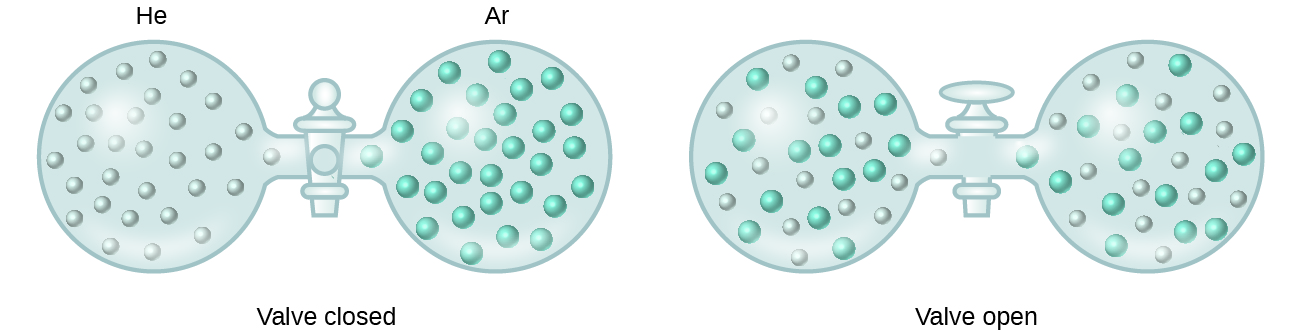

When the strengths of the intermolecular forces of attraction between solute and solvent species in a solution are no different than those present in the separated components, the solution is formed with no accompanying energy change. Such a solution is called an ideal solution . A mixture of ideal gases (or gases such as helium and argon, which closely approach ideal behavior) is an example of an ideal solution, since the entities comprising these gases experience no significant intermolecular attractions.

When containers of helium and argon are connected, the gases spontaneously mix due to diffusion and form a solution ( [link] ). The formation of this solution clearly involves an increase in disorder, since the helium and argon atoms occupy a volume twice as large as that which each occupied before mixing.

Ideal solutions may also form when structurally similar liquids are mixed. For example, mixtures of the alcohols methanol (CH 3 OH) and ethanol (C 2 H 5 OH) form ideal solutions, as do mixtures of the hydrocarbons pentane, C 5 H 12 , and hexane, C 6 H 14 . Placing methanol and ethanol, or pentane and hexane, in the bulbs shown in [link] will result in the same diffusion and subsequent mixing of these liquids as is observed for the He and Ar gases (although at a much slower rate), yielding solutions with no significant change in energy. Unlike a mixture of gases, however, the components of these liquid-liquid solutions do, indeed, experience intermolecular attractive forces. But since the molecules of the two substances being mixed are structurally very similar, the intermolecular attractive forces between like and unlike molecules are essentially the same, and the dissolution process, therefore, does not entail any appreciable increase or decrease in energy. These examples illustrate how diffusion alone can provide the driving force required to cause the spontaneous formation of a solution. In some cases, however, the relative magnitudes of intermolecular forces of attraction between solute and solvent species may prevent dissolution.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Chemistry' conversation and receive update notifications?