| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Mendel implied that only two alleles, one dominant and one recessive, could exist for a given gene. We now know that this is an oversimplification. Although individual humans (and all diploid organisms) can only have two alleles for a given gene, multiple alleles may exist at the population level, such that many combinations of two alleles are observed. Note that when many alleles exist for the same gene, the convention is to denote the most common phenotype or genotype in the natural population as the wild type (often abbreviated “+”). All other phenotypes or genotypes are considered variants (mutants) of this typical form, meaning they deviate from the wild type. The variant may be recessive or dominant to the wild-type allele.

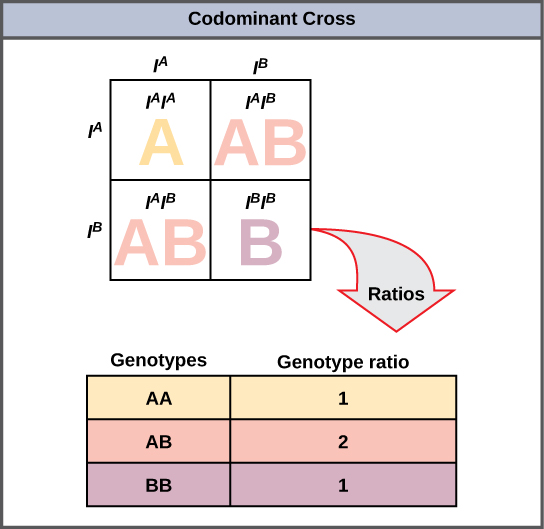

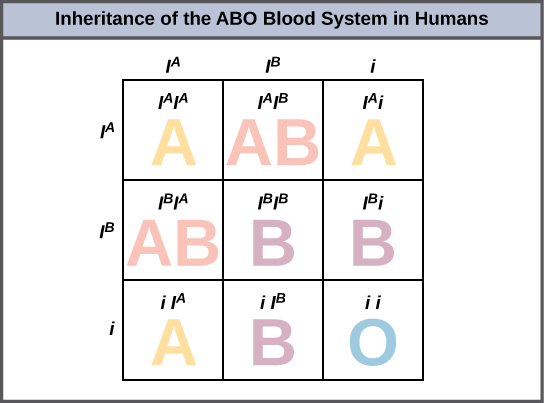

An example of multiple alleles is the ABO blood-type system in humans. In this case, there are three alleles circulating in the population. The I A allele codes for A molecules on the red blood cells, the I B allele codes for B molecules on the surface of red blood cells, and the i allele codes for no molecules on the red blood cells. In this case, the I A and I B alleles are codominant with each other and are both dominant over the i allele. Although there are three alleles present in a population, each individual only gets two of the alleles from their parents. This produces the genotypes and phenotypes shown in [link] . Notice that instead of three genotypes, there are six different genotypes when there are three alleles. The number of possible phenotypes depends on the dominance relationships between the three alleles.

In Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America, P. falciparum has developed resistance to the anti-malarial drugs chloroquine, mefloquine, and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine. P. falciparum , which is haploid during the life stage in which it is infective to humans, has evolved multiple drug-resistant mutant alleles of the dhps gene. Varying degrees of sulfadoxine resistance are associated with each of these alleles. Being haploid, P. falciparum needs only one drug-resistant allele to express this trait.

In Southeast Asia, different sulfadoxine-resistant alleles of the dhps gene are localized to different geographic regions. This is a common evolutionary phenomenon that comes about because drug-resistant mutants arise in a population and interbreed with other P. falciparum isolates in close proximity. Sulfadoxine-resistant parasites cause considerable human hardship in regions in which this drug is widely used as an over-the-counter malaria remedy. As is common with pathogens that multiply to large numbers within an infection cycle, P. falciparum evolves relatively rapidly (over a decade or so) in response to the selective pressure of commonly used anti-malarial drugs. For this reason, scientists must constantly work to develop new drugs or drug combinations to combat the worldwide malaria burden. Sumiti Vinayak et al., “Origin and Evolution of Sulfadoxine Resistant Plasmodium falciparum,” PLoS Pathogens 6 (2010): e1000830.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Concepts of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?