| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Watch a video of an artist’s impression of matter accreting around a supermassive black hole.

In order to prove that a black hole is present at the center of a galaxy, we must demonstrate that so much mass is crammed into so small a volume that no normal objects—massive stars or clusters of stars—could possibly account for it (just as we did for the black hole in the Milky Way). We already know from observations (discussed in Black Holes and Curved Spacetime ) that an accreting black hole is surrounded by a hot accretion disk with gas and dust that swirl around the black hole before it falls in.

If we assume that the energy emitted by quasars is also produced by a hot accretion disk , then, as we saw in the previous section, the size of the disk must be given by the time the quasar energy takes to vary. For quasars, the emission in visible light varies on typical time scales of 5 to 2000 days, limiting the size of the disk to that many light-days.

In the X-ray band, quasars vary even more rapidly, so the light travel time argument tells us that this more energetic radiation is generated in an even smaller region. Therefore, the mass around which the accretion disk is swirling must be confined to a space that is even smaller. If the quasar mechanism involves a great deal of mass, then the only astronomical object that can confine a lot of mass into a very small space is a black hole. In a few cases, it turns out that the X-rays are emitted from a region just a few times the size of the black hole event horizon.

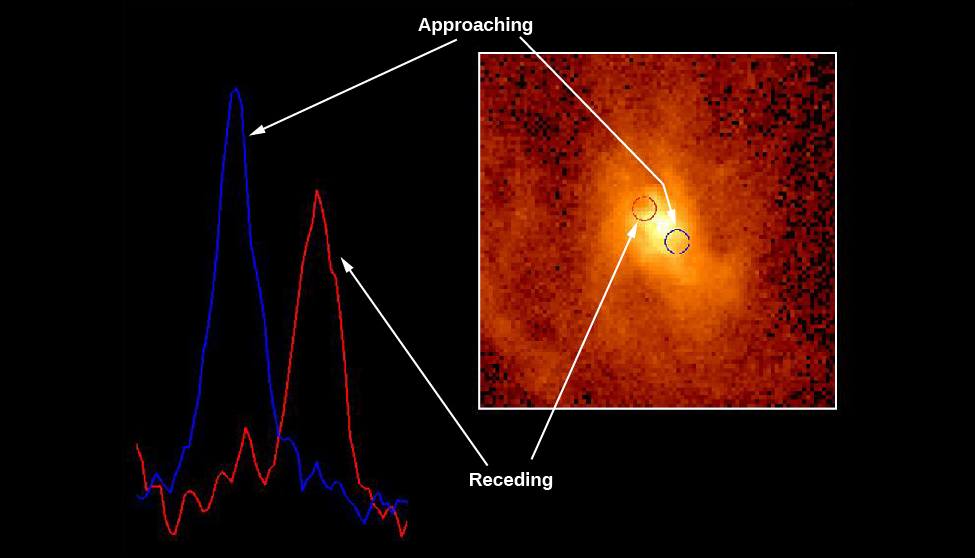

The next challenge, then, is to “weigh” this central mass in a quasar. In the case of our own Galaxy, we used observations of the orbits of stars very close to the galactic center, along with Kepler’s third law, to estimate the mass of the central black hole ( The Milky Way Galaxy ). In the case of distant galaxies, we cannot measure the orbits of individual stars, but we can measure the orbital speed of the gas in the rotating accretion disk. The Hubble Space Telescope is especially well suited to this task because it is above the blurring of Earth’s atmosphere and can obtain spectra very close to the bright central regions of active galaxies. The Doppler effect is then used to measure radial velocities of the orbiting material and so derive the speed with which it moves around.

One of the first galaxies to be studied with the Hubble Space Telescope is our old favorite, the giant elliptical M87 . Hubble Space Telescope images showed that there is a disk of hot (10,000 K) gas swirling around the center of M87 ( [link] ). It was surprising to find hot gas in an elliptical galaxy because this type of galaxy is usually devoid of gas and dust. But the discovery was extremely useful for pinning down the existence of the black hole. Astronomers measured the Doppler shift of spectral lines emitted by this gas, found its speed of rotation, and then used the speed to derive the amount of mass inside the disk—applying Kepler’s third law.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?