| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The grains that condensed in the solar nebula rather quickly joined into larger and larger chunks, until most of the solid material was in the form of planetesimals, chunks a few kilometers to a few tens of kilometers in diameter. Some planetesimals still survive today as comets and asteroids. Others have left their imprint on the cratered surfaces of many of the worlds we studied in earlier chapters. A substantial step up in size is required, however, to go from planetesimal to planet.

Some planetesimals were large enough to attract their neighbors gravitationally and thus to grow by the process called accretion . While the intermediate steps are not well understood, ultimately several dozen centers of accretion seem to have grown in the inner solar system. Each of these attracted surrounding planetesimals until it had acquired a mass similar to that of Mercury or Mars. At this stage, we may think of these objects as protoplanets —“not quite ready for prime time” planets.

Each of these protoplanet s continued to grow by the accretion of planetesimals. Every incoming planetesimal was accelerated by the gravity of the protoplanet, striking with enough energy to melt both the projectile and a part of the impact area. Soon the entire protoplanet was heated to above the melting temperature of rocks. The result was planetary differentiation , with heavier metals sinking toward the core and lighter silicates rising toward the surface. As they were heated, the inner protoplanets lost some of their more volatile constituents (the lighter gases), leaving more of the heavier elements and compounds behind.

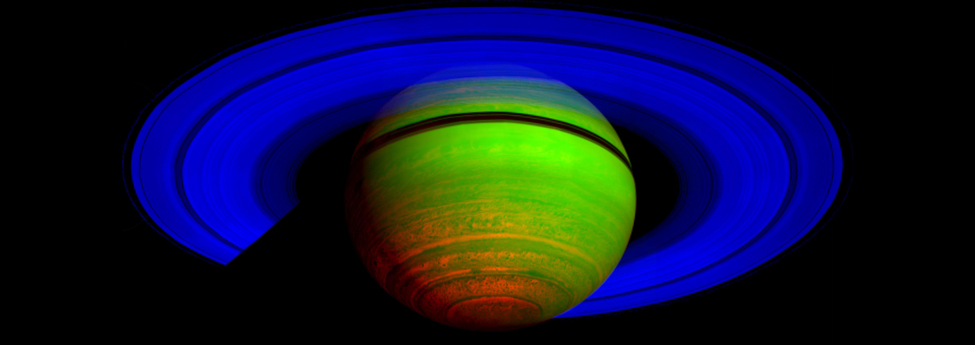

In the outer solar system, where the available raw materials included ices as well as rocks, the protoplanets grew to be much larger, with masses ten times greater than Earth. These protoplanets of the outer solar system were so large that they were able to attract and hold the surrounding gas. As the hydrogen and helium rapidly collapsed onto their cores, the giant planets were heated by the energy of contraction. But although these giant planets got hotter than their terrestrial siblings, they were far too small to raise their central temperatures and pressures to the point where nuclear reactions could begin (and it is such reactions that give us our definition of a star). After glowing dull red for a few thousand years, the giant planets gradually cooled to their present state ( [link] ).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?