| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By 1790, an orbit had been calculated for Uranus using observations of its motion in the decade following its discovery. Even after allowance was made for the perturbing effects of Jupiter and Saturn, however, it was found that Uranus did not move on an orbit that exactly fit the earlier observations of it made since 1690. By 1840, the discrepancy between the positions observed for Uranus and those predicted from its computed orbit amounted to about 0.03°—an angle barely discernable to the unaided eye but still larger than the probable errors in the orbital calculations. In other words, Uranus just did not seem to move on the orbit predicted from Newtonian theory.

In 1843, John Couch Adams , a young Englishman who had just completed his studies at Cambridge, began a detailed mathematical analysis of the irregularities in the motion of Uranus to see whether they might be produced by the pull of an unknown planet. He hypothesized a planet more distant from the Sun than Uranus, and then determined the mass and orbit it had to have to account for the departures in Uranus’ orbit. In October 1845, Adams delivered his results to George Airy, the British Astronomer Royal, informing him where in the sky to find the new planet. We now know that Adams’ predicted position for the new body was correct to within 2°, but for a variety of reasons, Airy did not follow up right away.

Meanwhile, French mathematician Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier , unaware of Adams or his work, attacked the same problem and published its solution in June 1846. Airy, noting that Le Verrier’s predicted position for the unknown planet agreed to within 1° with that of Adams, suggested to James Challis, Director of the Cambridge Observatory, that he begin a search for the new object. The Cambridge astronomer, having no up-to-date star charts of the Aquarius region of the sky where the planet was predicted to be, proceeded by recording the positions of all the faint stars he could observe with his telescope in that location. It was Challis’ plan to repeat such plots at intervals of several days, in the hope that the planet would distinguish itself from a star by its motion. Unfortunately, he was negligent in examining his observations; although he had actually seen the planet, he did not recognize it.

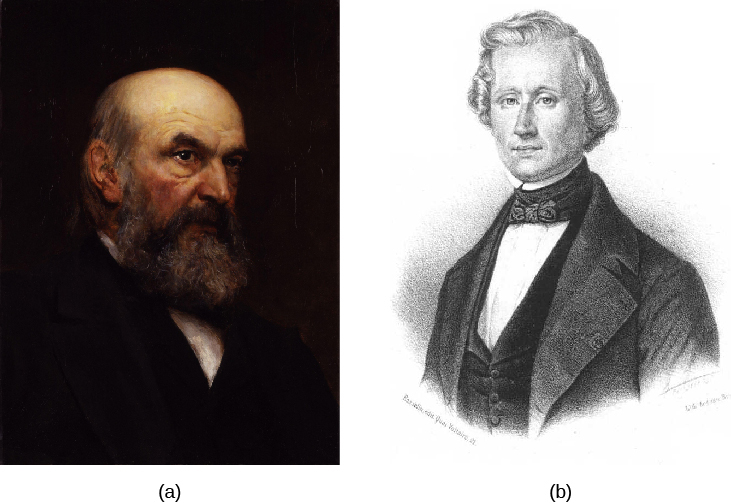

About a month later, Le Verrier suggested to Johann Galle , an astronomer at the Berlin Observatory, that he look for the planet. Galle received Le Verrier’s letter on September 23, 1846, and, possessing new charts of the Aquarius region, found and identified the planet that very night. It was less than a degree from the position Le Verrier predicted. The discovery of the eighth planet, now known as Neptune (the Latin name for the god of the sea), was a major triumph for gravitational theory for it dramatically confirmed the generality of Newton’s laws. The honor for the discovery is properly shared by the two mathematicians, Adams and Le Verrier ( [link] ).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?